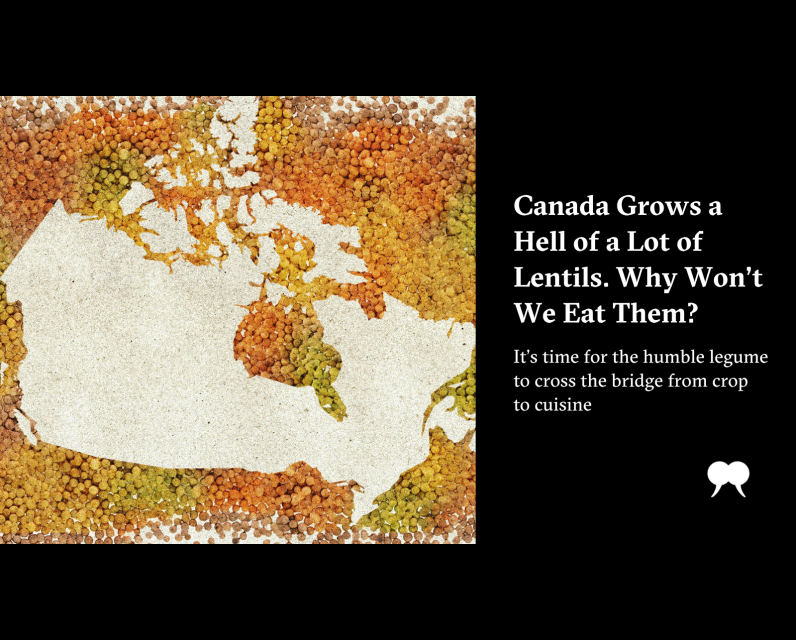

Canada Grows a Hell of a Lot of Lentils. Why Won’t We Eat Them?

For lentil growers, 2016 was a heady time. Or, at least, as heady as it can get in the world of lentils. Normally, the humble, stodgy legume doesn’t garner much attention, let alone celebration, at least not in Canada. But the high-fibre staple food of the hippie roommate was in the midst of a marketing push. The United Nations dubbed it the International Year of Pulses.

The UN does this every few years: they declare it the “Year” of an important food. Rice got the honour in 2004. In 2008, potatoes were celebrated for their bold conquest—only a few centuries ago, the spud escaped its Andean roots and became a global hit. In the 2010s, at the peak of kale salad and eating à la Gwyneth, the UN’s picks took on the sheen of wellness: 2013, for instance, was quinoa. When pulses—the edible seeds of lentils, chickpeas, beans, and other legumes—got their turn in the spotlight, they were promoted for their nutritional value and environmental benefits.

Meanwhile, in Canada, the lentil harvest was peaking. In Saskatchewan, more land was being seeded than ever before. Exports were booming—India (the country that swallows half the world’s supply) bought more than a billion dollars’ worth of pulses from Canada in 2016.

Canada was well settled as the world’s top lentil producer. From its infancy in the 1970s and ’80s, the lentil industry has grown dramatically year after year. In 1973, production was virtually nil. By 2016, it was hard to overstate just how much of the global market was in the hands of the Saskatchewan farmer. More than 3 million tonnes of lentils were grown in Canada that year, accounting for nearly half of the total global output.

If there was a race to become the kingpin of the global lentil market, Canada had won it. A drought or infestation in Saskatchewan would be felt on the tables of Delhi, Karachi, and Dhaka. But, ironically, not so much at home.

Canadians, as a whole, are not a lentil-eating people. Yes, some of us eat dal several times a week. But others can’t remember the last time they ate a lentil. How can it be that the country that grows the most lentils in the world eats so few?

The International Year of Pulses was as good a time as any to make a play for the average Canuck’s dinner plate. The industry association, Pulse Canada, came up with a marketing campaign. “Take the Pulse Pledge,” they said: eat pulses once a week for ten weeks to discover just how delicious and versatile the little things can be. There are iridescent black lentils used for making dal makhani. Yellow ones can be boiled with a ham bone to make something akin to split pea soup. There are tiny red lentils that cook in twenty minutes without having to be soaked. And the large, flat green ones, called Laird lentils, have become particularly popular among Prairie farmers.

Michael Smith became a pitchman. He was already known in lentil marketing circles, having hosted a globe-trotting web series called Lentil Hunter for Saskatchewan Pulse Growers. The Prince Edward Island chef and Food Network regular appeared in media segments pitching fritters and dal to morning show hosts.

Smith’s pitch was broad, and he delivered it with his characteristic practised enthusiasm. Lentils are packed with fibre and micronutrients! They’re easy on the wallet, easy to cook, and easy on the planet! Best of all, Smith promised in his pitch, lentils taste great.

Needless to say, the effort didn’t transform the Canadian diet. But it did get the word out. Lentils got another notable endorsement in 2019, when the newly revised Canada’s Food Guide explicitly recommended eating more plant protein like lentils and beans.

A 2024 University of Saskatchewan report on consumer attitudes toward lentils cited survey data suggesting that plenty of Canadians (an estimated 6.4 million in 2018) want to eat less meat. In a survey by food policy professor Sylvain Charlebois, the majority of respondents had considered reducing their consumption. But only 32 percent were actually willing to do it in the near future. We tell ourselves we ought to be eating more beans and lentils, more plant protein, but in practice, our diets are ingrained in habit and culture, making them resistant to change.

It’s a culinary oddity: we grow something consumed in massive quantities around the world but don’t really consider it a staple of the mainstream Canadian diet despite decades of dominating global production. Lentils don’t read as a particularly Canadian food. In and of itself, this isn’t a problem. But it is a looming vulnerability.

The fate of Canada’s lentil growers hangs on the whims of the South Asian market and the mood of foreign governments. Over the past decade, India has imposed on-again, off-again tariffs on Canadian lentil imports. Even when tariffs were lowered, the threat was always there. Saskatchewan lentil farmers plant their crops in spring, not knowing if there will be a market collapse come fall. In 2016, 5.5 million acres in Canada were devoted to lentil production, largely in the prairie province. By 2018, the number had dropped to under 4 million. The amount of seeded land has fluctuated every year since the dip, but it has never returned to the highs of 2016.

If we in Canada were eating more of our own supply, it would ease the pressure, says Tanya Der of Pulse Canada. She says finding new markets for Canadian lentils is an endless mission, and one of the biggest untapped markets is right here at home. Der adds that the growth will most likely happen in what she calls “value-added” products: lentil-based chips, crackers, energy bars, pasta.

Chef Smith’s pulse taco didn’t spur lentil love to new heights. But perhaps the moment is now. The lentil may still crack the patriotic grocery list amid all the “elbows up” posturing. In a time of renewed nationalism and “Buy Canadian” rhetoric, maybe the lentil has a chance to occupy a cultural space beside maple syrup or rye whisky.

The Vancouver-based chef and restaurateur Vikram Vij has been selling dal since the ’90s, a time when he had to explain that lentils didn’t have to play a supporting role for meat. “The French chefs would take lentils with rosemary and cream and then put a steak on top of it,” he says. “It was always a side dish.”

Now, he says, lentils are beginning to show up everywhere, from airport lounges to prepared food counters at the supermarket. “You go to supermarkets twenty years ago and you would not find a lentil salad. Now everyone has a lentil salad in their showcase.”

Think, too, of the now-ubiquitous plastic tubs of hummus at the supermarket (including a chocolate-flavoured one) that were “ethnic” oddities not even a generation ago. Now, you’d be hard pressed to find a potluck that doesn’t feature, at the very least, a fridge-cold container of hummus alongside a plate of baby carrots.

For centuries, foreign foods have been bent to the whims of local tastes in countless ways. Consider sushi, once an exclusively Japanese speciality; then a marker of urban elitism; now in every food court, supermarket, and airport cafe. Even pizza, now inescapable, was once unknown to even the most urbane Canadian. Now, we invent versions that would be unknown to any Italian.

We’ve been making local things out of foreign things for generations in Canada, a land where people have been arriving with their own culinary customs in tow for the past 400-odd years.

At my local grocer, lentils sit on a low shelf in an out-of-the-way aisle. For real variety, I skip the big-name supermarkets. The Middle Eastern and South Asian markets are where the shelves groan under the weight of dozens of types, each with its own character. Health food stores, too, offer a rainbow in wooden bins: bright orange, canary yellow, olive green, nearly black. Given enough time, masoor dal (spiked with a tadka of garlic, mustard seeds, and chilies) may become as Canadian a food as the butter tart.

The post Canada Grows a Hell of a Lot of Lentils. Why Won’t We Eat Them? first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment