Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Eve Lazarus

Publication Date: July 5, 2025 - 06:30

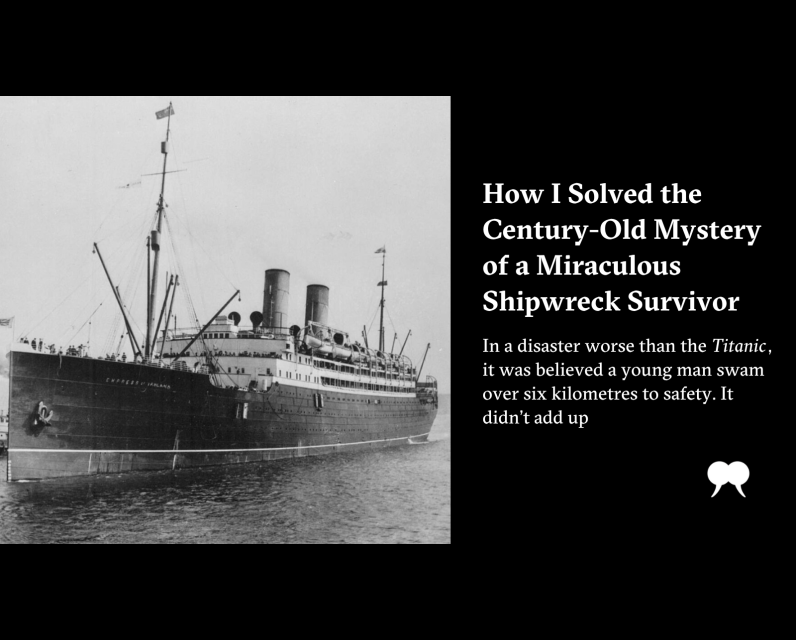

How I Solved the Century-Old Mystery of a Miraculous Shipwreck Survivor

July 5, 2025

I t’s the morning of August 22, 2019, and I’m in a Zodiac bouncing along the waters of the St. Lawrence River. It can hold six divers and all their gear, but this morning, there are only six of us—no gear. Far from being divers, we are curiosity seekers from New York, Vancouver, London, and Montreal, all obsessed with the sinking of the Empress of Ireland, which claimed 1,014 lives in 1914.

Until a few years ago, I had never heard of the Empress and its disastrous end. And that’s staggering, because the loss of passenger life (836) outnumbered that of the Titanic (832).

The Empress, owned by the all-powerful Canadian Pacific Railway, carried more than 117,000 people between Liverpool, England, and Saint John, New Brunswick, and later Halifax or Quebec City, depending on the season, in ninety-six round trips between 1906 and 1914. A million or so Canadians from coast to coast can trace their roots back to an ancestor who came to Canada on this ship.

Every schoolchild knows the story of the Titanic, the luxury ocean liner that hit an iceberg and sank in 1912. So why did the Empress tragedy, which claimed even more passenger lives a little over two years later, fail to embed itself in our collective national consciousness?

Likely it’s because, while the Titanic was filled with big names from the New York social register, the Empress was a comfortable workhorse filled with ordinary Canadians. Most of those who drowned were in the third-class hold, and a large number of them were immigrants and labourers. It wasn’t the maiden voyage, people didn’t want to think that these ships were vulnerable, and in most people’s minds, the Empress liners were synonymous with safety, reliability, and comfort.

On May 28, 1914, the Empress began her 192nd trip across the Atlantic, from Quebec City en route to Liverpool, carrying 1,056 passengers and a crew of 423. In the early hours of May 29, fog descended on the St. Lawrence River, and the ocean liner was rammed by the Storstad, a Norwegian coal ship. There was time to launch only four of the forty lifeboats, and rather than women and children first, it was everyone for themselves in the fourteen minutes it took for the Empress to sink.

In just thirty seconds, the Empress took on almost half her own weight in water.

A century later, on this late-August day in 2019, I’m sitting next to Hugh Verrier, a New York lawyer who heads up one of the world’s largest law firms and who is responsible for our trip out to the wreck. Verrier is originally from Montreal, and since the 1920s, his family has owned a summer property near Rimouski, close to where the Empress sank. He swims in the St. Lawrence River most summers and has always known about the tragedy, but in recent years, he has developed a fascination for the story of survivor Gordon Charles Davidson.

Davidson was a PhD candidate from Union, Ontario, who lived in Vancouver when he wasn’t studying at UC Berkeley in San Francisco and was travelling on the Empress for a study trip. He had reportedly survived the sinking of the Empress by swimming six and a half kilometres to shore. When Verrier looked into it, experts told him this wasn’t possible—not at that time of year and not for that distance. But he wanted to make sure. He wanted to verify the information that had been repeated in newspaper articles and regurgitated in books and even at Davidson’s own memorial service almost a century before. Whatever happened, Verrier wanted to set the record straight.

In November 2017, Verrier hired me to research Davidson. In an email to me, he attached Davidson’s 1922 obituary, an article about his miraculous swim to shore, and a photo of him receiving medical treatment at the Château Frontenac following the shipwreck.

“I have not found any record of him speaking or writing about swimming to shore,” Verrier wrote. “He did not have any children. So, this is not going to be easy to find out about.” He wasn’t wrong.

O n the morning of May 28, 1914, the port at Quebec City was buzzing with activity. Nearly 3,000 immigrants, tourists, and returning Canadians would disembark from seven different ocean liners that day, and workers were unloading the cargo from two colliers that carried coal from Cape Breton to Montreal. The Dominion Coal Company operated fourteen colliers, including the Norwegian-registered Storstad.

The RMS Empress of Ireland towered above the wharf. She was 14,191 tons of Edwardian elegance. She had been in Quebec City for five days, and this next sail would be her 192nd trip across the Atlantic. She was under the command of the newly promoted Captain Henry George Kendall, the youngest captain of the large Atlantic liners. It would be his third crossing as commander of the Empress. On May 1, he had taken the ship from Halifax—the Canadian winter terminal—to Liverpool and returned via the Gulf of St. Lawrence and up the now thawed St. Lawrence River to Quebec City. The trip out had been uneventful, and the Empress had arrived safely at port with 1,100 passengers aboard.

Passengers gathered on the deck of the Empress of Ireland, circa 1910 (City of Vancouver Archives, Am54-S4-:Bo P117)

Now, by 1:30 a.m. on May 29, the Empress was past the most dangerous part of the St. Lawrence River and going about seventeen knots (thirty-one kilometres per hour). John Carroll, the lookout, rang the crow’s nest brass bell once to notify the bridge of a vessel on the starboard side. Kendall took the stairs to the compass platform for a better view. He could see the distant lights of an incoming ship—the Storstad—and estimated that it was about ten kilometres away. The weather was clear and fine, and Kendall saw no reason for concern.

A little while later, a thick bank of fog rolled in from the south shore, slowly creeping across the water in a northwest direction and blanketing the Empress and the Storstad. Both ships were now hidden from each other. Moments later, Kendall was standing on the navigation bridge, staring in horror as the Storstad ’s bow emerged from the fog and headed straight toward them. The collier rammed the passenger ship dead centre, slicing through the Empress.

The Storstad was on its way to Montreal, carrying more than 10,000 tons of coal. She had a reinforced hull that could slice through winter ice, and at that moment, she was headed to Father Point to collect a pilot who would navigate the ship up the St. Lawrence. Her sharp prow ripped through the Empress ’s steel plates and cabins, tearing a 32.5-square-metre hole in the ship’s starboard side, well below the waterline.

More than 200,000 litres of water a second poured into the Empress, causing catastrophic flooding in the engine rooms and lower decks. The furnaces flooded. The power went out.

The ship was thrown into darkness before most of the sleeping passengers could even grasp what was happening. Those who had managed to leave their cabins were left groping around in the pitch dark, trying to find a way out, clawing their way up the tilting stairs. Because they had boarded the ship mere hours earlier, they were unfamiliar with the ship’s layout. In just thirty seconds, the Empress had taken on almost half her own weight in water. After a minute and a half, the boiler rooms were flooded with the equivalent of nine Olympic swimming pools of water.

G ordon Charles Davidson was a good-looking, serious young man of twenty-nine. He had dark hair, dark-brown eyes, and an athletic build and stood just shy of six feet. Later he would grow a moustache, but for this trip across the Atlantic, he was clean shaven and wore his hair parted slightly to the left in an attempt to smooth down an unruly cowlick that had dogged him since childhood.

Davidson had spent his childhood on the family farm in Union in the Elgin County of Ontario. After finishing high school, he moved to Vancouver to study.

Gordon Charles Davidson, survivor of the Empress of Ireland sinking, circa 1913 (Courtesy of Margaret Patmore)

When Verrier hired me to research Davidson and the story of his miraculous swim, the first thing I did was put together a family tree. Davidson had not had children, but his older brother, James, had three, and that seemed like a good place to start.

I tracked James’s granddaughter down to her home in Madrid, Spain. Not only is she the keeper of the Davidson family history, she had Davidson’s actual survival account in the form of a century-old torn-up newspaper clipping. The problem was that the name of the newspaper that it was printed in was mostly torn out and only identified as “—as Journal.” The headline was “Local Boy Tells a Graphic Story of Fight with Death When Empress Went Down.”

With the help of my friend Tom Carter, a Vancouver artist and historian, we were able to track the article to the St. Thomas Journal, a newspaper that had merged with the St. Thomas Daily Times in 1918 to become the St. Thomas Times-Journal, which still publishes. Unfortunately, none of its early issues had been digitized. Gina Dewaele at the Elgin County Archives found Davidson’s letter printed in full in the St. Thomas Journal of June 2, 1914.

When Davidson reached Quebec City, he saw that early newspaper reports had listed him among the missing. He immediately sent a telegram to his father in Union, letting him know that he was safe. His father contacted James, in Vancouver. James then gave an interview to a reporter, and somehow the story of Davidson’s survival got blown out of proportion. The story, which appeared in the Vancouver Province on June 1, 1914, ran with the headline “He Swam Ashore as Empress Sank.”

Just four weeks after it had claimed front-page headlines, the tragedy abruptly disappeared from newspapers.

“If the report that he swam ashore is correct, he performed a really wonderful feat,” wrote the reporter. “From the meagre particulars of Mr. Davidson’s escape received by his brother here, his experiences may be pictured. The boat sinking with its hundreds of passengers pitched into the water all struggling for life; the frantic attempt to seize the boats or to secure a piece of wreckage on which to float to safety, can be imagined.”

The story goes on to say that, after seeing the lifeboats were filled to capacity, Davidson kept swimming until he was too far out for rescue and instead decided to swim to shore. It ends with the reporter noting that Davidson was a strong swimmer and had managed to find a lifebelt.

I n reality, Davidson woke to the sound of rushing water on that night on the Empress. At first, he thought it was the crew flushing out the decks, but the noise was too loud. He turned on the electric light and was horrified to see water flowing into his cabin.

“Even then, I hardly realized what was wrong, but [Arthur] Stillman [with whom Davidson was sharing a room] called that we were sinking and rushed out, and I followed in my nightshirt. By that time, the water was half filling the cabin,” Davidson’s account in the St. Thomas Daily Times reads. “As I stepped into the passageway, a stream of water from the open porthole struck me between the shoulders and knocked me down. The water was spouting in there in a foot-wide stream that was 15 feet long. I scrambled on my hands and knees till I got beyond it. Then I climbed up two flights of stairs till I got to the saloon deck, where I braced myself against a door. The bow dipped under first, and she had listed so far that it was like a level floor when I ran down her side and dived off the keel.”

Davidson stripped off his nightshirt and swam away from the ship. The suction took him down, and when he came up, he swam into a frenzied crowd. “They tramped me under three times before I got through them. I swam on a little farther, but the water was fearfully cold, and I was out of practice swimming,” he said.

Davidson was picked up by a lifeboat and taken to the Storstad, which survived the collision.

Dr. James Grant tending to Gordon Davidson after the Empress tragedy (Library of Congress, LC-B2-3078-15)

None of what appeared in the Vancouver Province actually happened. It was all one reporter’s wild speculation. And even though Davidson tried to correct the information himself, that one reporter’s version from two days after the shipwreck is what was repeated and embellished in newspaper articles, in books, and even in his own obituary eight years later.

Just four weeks after the tragedy had claimed front-page headlines around the world, the Empress of Ireland abruptly disappeared from newspapers. On June 28, 1914, Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophia, were shot dead in Bosnia. By the following month, much of the world was at war. And many of those young men who had narrowly escaped death on the Empress, including Davidson, would soon face an even bigger threat: four years of unprecedented carnage, slaughter, and destruction.

Adapted and excerpted, with permission, from Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck by Eve Lazarus, published by Arsenal Pulp Press, 2025. The post How I Solved the Century-Old Mystery of a Miraculous Shipwreck Survivor first appeared on The Walrus.

When the rainclouds burst over Vancouver one grey day this past winter, Lon LaClaire was delighted to see floodwater streaming into newly terraced pools on the side of a steep hill in an east-side neighbourhood.Mr. LaClaire, Vancouver’s chief engineer, is part of a team that has been working to ensure much of the city’s abundant rain does not end up flooding through the sewer system, sweeping everything from road debris and toxic chemicals into surrounding waterways – False Creek, Burrard Inlet, the Fraser River – along with it.

July 5, 2025 - 09:30 | Frances Bula | The Globe and Mail

Canada's environment ministers back tougher air quality standards, citing wildfire smoke and rising health risks from fine particulate pollution.

July 5, 2025 - 08:52 | Prisha Dev | Global News - Canada

B.C. infrastructure Minister Bowinn Ma says she won't be deterred after a blast at her office and highlights growing concerns over safety for elected officials.

July 5, 2025 - 08:46 | Globalnews Digital | Global News - Canada

Comments

Be the first to comment